trending topics

market reports

-

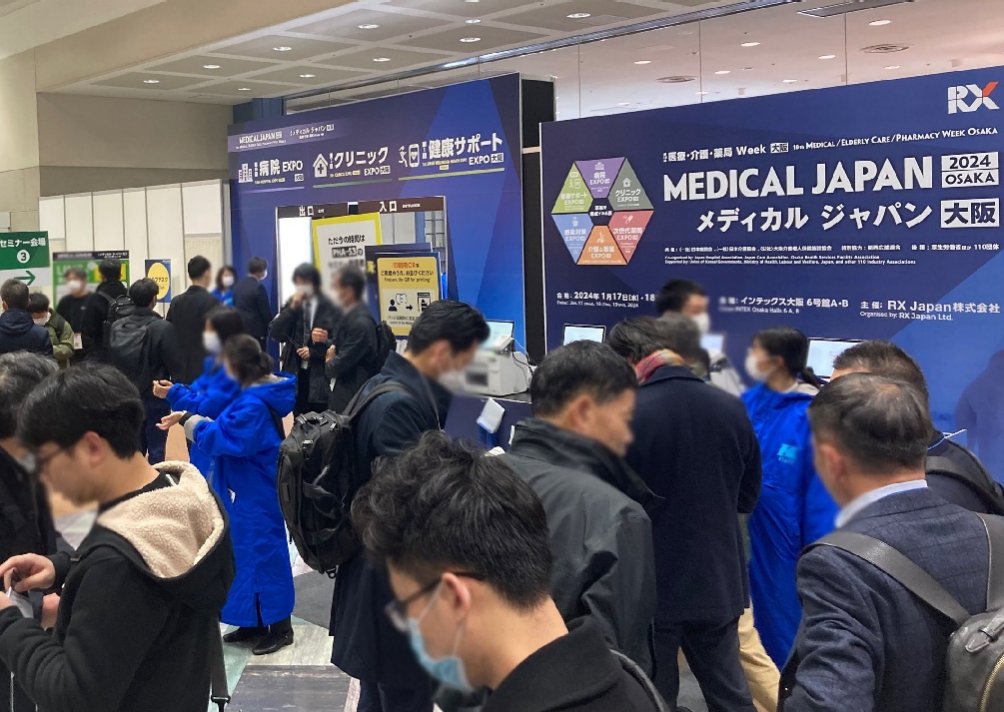

MEDICAL JAPAN 2025 OSAKA Returns to Showcase Global Innovations

2025-02-17

-

Visit MEDICAL JAPAN 2023 TOKYO and take full advantage of the business opportunities!

2023-09-01

-

US to distribute 400 million free N95 masks at CVS, Walgreens in COVID fight

2022-01-21

-

Ethiopia receives additional 2.2 mln doses of Chinese-donated COVID-19 vaccines

2022-01-21

-

Hong Kong researchers say they develop novel material able to kill COVID-19 virus

2022-01-14

-

10 million more Chinese doses on way for Kenya

2022-01-14

-

Sino-African ties on track for a brighter future

2022-01-07

-

Efforts urged to boost COVID-19 vaccine production capacity in poor countries

2022-01-07

-

UAE approves Sinopharm's new protein-based COVID-19 vaccine

2022-01-07

-

UAE approves Sinopharm's new protein-based COVID-19 vaccine

2022-01-07

Trials of a vaccine and new drug raise hope of beating covid-19

2020-07-28

IN EARLY JANUARY researchers at Oxford University started work on a vaccine for covid-19. At that time the illness was a tiny outbreak without a proper name. Six months on, with more than 600,000 people dead, the Oxford team is leading a race to develop a vaccine that could halt the pandemic. The vaccine has been raced into production around the world by AstraZeneca, a British-Swedish drug company, and billions of doses are planned. But two key questions remain: is it safe and does it work? The first glimmers of the answers have just arrived, with the publication in the Lancet on July 20th of a paper about a trial of the Oxford vaccine, which began in April and involved 1,000 volunteers.

According to Adrian Hill, director of Oxford’s Jenner Institute and one of the authors of the paper, the new vaccine stimulated a strong immune response and appears to be well tolerated and safe. It generated both antibodies and “an excellent” T-cell response. Antibodies and T-cells are the two principal arms of the immune system. The former recognise, lock onto and disable pathogens. The latter recognise and kill infected body cells, to stop viruses reproducing inside them. Dr Hill says that the antibody levels seen in the trial are similar to those observed in natural infections and that the T-cell responses are “very high”. They are also, he says, “clearly better” than those from another vaccine being developed by Moderna, an American biotechnology firm.

This good response from T-cells will reassure those who are concerned that some patients who have recovered from covid-19 show rapidly waning levels of natural antibodies. A waning antibody response might mean that the immune system does not remember its infection, which would bode poorly for a vaccine’s success. Infection with some viruses, such as those that cause the common cold, do not provide lasting immunity.

T-cells may be particularly important for fighting covid-19 because it seems that they may generate a very long-lasting immunity. Recent research from Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore showed that patients infected with SARS, during the outbreak 17 years ago of that then-novel virus, still possessed T-cell- based immune memory of their infection. SARS-CoV-2, the virus which causes covid-19, is, as its name suggests, a close relative of that original SARS virus.

Positive results have now been reported from early-stage trials of four vaccines. As well as Moderna, Pfizer, a big pharmaceuticals company, had already published data. CanSino biologics, a Chinese company, reported on the same day as Oxford. This will fuel optimism that a successful vaccine may be available by the end of the year. The results from trials are encouraging, yet what all the data mean in terms of providing protection against covid-19 is hard to say. Both antibodies and T-cells are generally necessary to provide immunity—and there is a suspicion that T-cells might be particularly important in mitigating excessive immune responses. It will, however, take the completion of efficacy trials to work out whether any of these vaccines provide useful levels of protection.

The Oxford vaccine is furthest ahead with such trials. A 10,000-patient trial in Britain has almost finished recruiting, and recruitment is rising quickly for a trial in Brazil. Trials in South Africa have just started, and another will begin in America in the coming weeks. If everything goes well it could be clear to researchers by the end of August whether or not the vaccine works. When the results of the first of these trials are available, assuming they are positive, regulators will have to decide whether there are enough data to allow for some sort of emergency approval before further trials are conducted. That could happen as early as October.

As for which vaccine will be most effective, it is, at this stage, difficult to compare the different versions. But eventually such a comparison will need to be made. For that to be done, the immune responses from each vaccine will have to be measured in the same laboratory.

The news from Oxford came on the same day as the announcement of a possible drug treatment for covid-19. Synairgen, a small British biotechnology company, said it will soon present findings that its inhaled form of a substance called interferon beta is effective. When this drug was given to those with the illness in a trial involving 100 patients (small, by the standards of these things), it significantly reduced the numbers who then went on into intensive care. The odds of requiring ventilation were reduced by 79% and patients were two to three times more likely to recover.

Outsiders have urged caution in interpreting these results, because Synairgen has not yet released information about how it conducted its trial or what sort of patients were recruited into it. Nor have the findings been peer-reviewed. However, if the claims made are confirmed, this work would represent an important advance in the ability to treat covid-19. Taken together, then, these two announcements add to hope that science will provide an exit strategy for covid-19 some time this year.

(The Economist)

My Member

My Member Message Center

Message Center